This post is written by Mary Chase, Ph.D., an expert in curriculum design, literacy education, and technology integration.

Years ago, when I first entered the classroom, I thought I knew my subject area and I thought I knew how to teach. You won’t be surprised to learn that, while my head was stuffed with facts and learning strategies, I really knew nothing about either area. Dewey teaches that we learn by doing and that is nowhere more true than in the field of teaching. Further, all my training, all the demands of my job and the expectations of my administrators, parents and students were defined by curriculum. Nobody said much about learning, let alone thinking.

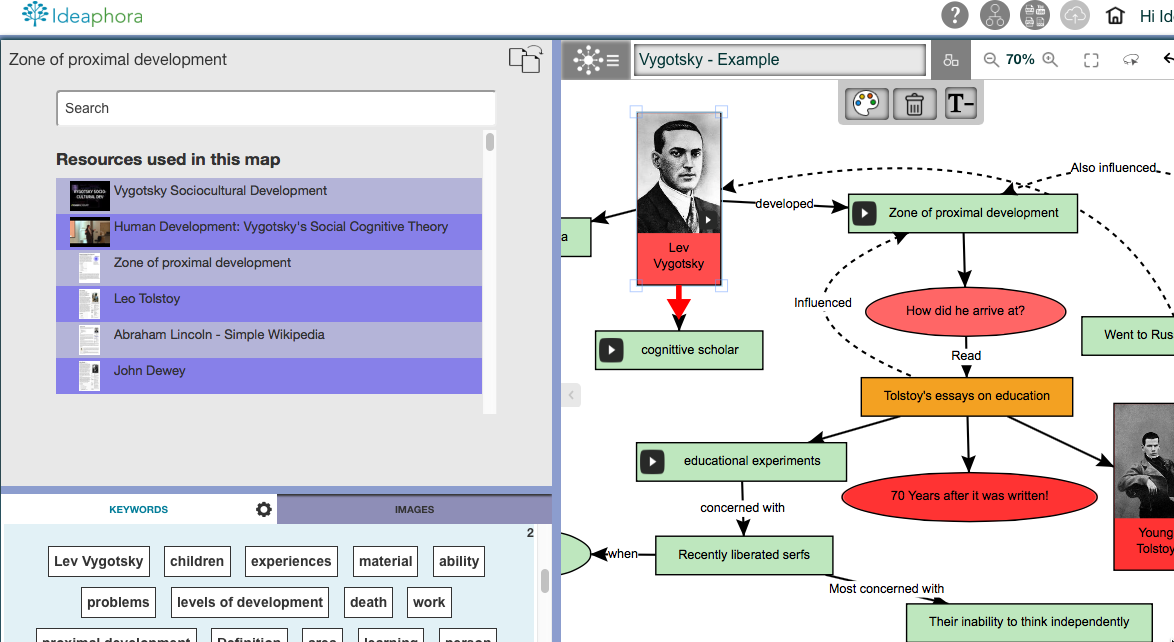

Later, in graduate school, I discovered the work of cognitive psychologist, Vera John-Steiner, and her works became seminal to my own ideas about the role of thinking in education. John-Steiner’s first contribution to the field, Notebooks of the Mind: Explorations of Thinking, centered on the cognitive habits of geniuses from science, art, writing, music—all of the humanities—based on a close analysis of their journals, personal accounts and conversations. Leo Tolstoy, Marie Curie, Diego Rivera—over 50 geniuses account for their creative visions. Her investigation is accompanied by her own insights on the nature of thinking. She writes, “Thought is embedded in the structure of the mind. One way to think of this structure is to view it as formed by networks of interlocking concepts of highly condensed and organized clusters of representations.”