This post is written by Mary Chase, Ph.D., an expert in curriculum design, literacy education, and technology integration.

A good friend of mine, Tim Gillespie, once said, “Anytime you do something for students that they could do for themselves, you are 1) working too hard, and 2) stealing from them an opportunity for learning.” I’ve carried this notion with me and rediscovered every year just how capable and creative my students can be.

I remembered Tim’s insight last week when I read the Ideaphora Blog about vetting open education resources (OER). Why not take advantage of this opportunity to refine students’ existing digital literacy skills in search of useful classroom resources?

There is an overabundance of information online that students are increasingly able to access anytime, anywhere through smartphones, tablet computers, and other digital devices. But despite their web-savvy reputations, most students have difficulty efficiently and effectively searching for high-quality, verified resources.

According to the Pew Research Center survey of middle and high school AP teachers and National Writing Project communities, the vast majority of teachers say it should be a top priority to teach students online research skills. In most cases, teachers rated the research skills of their students only as “good” or “fair” with very few rating their students' skills as “excellent.”

Previously, we highlighted the role of high-quality information sources in the successful construction of knowledge maps. After all, their maps can be no better than the information they draw on.

It's critical to explicitly teach online research skills, such as how to evaluate a website's credibility, how to use precise keywords, and how to better mine search engines and databases. The NCTE and ILA national standards, as well as Common Core, require students to learn how to use a variety of technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

Coupling Ideaphora with Google’s Advanced Search feature can help teachers and students do just that. Google is by far the most frequently used tool that teachers and students use for online research. Google’s Advanced Search is an under-utilized resource that’s easy-to-use and extremely efficient. Advanced searches can lead students to more reliable information, and help them avoid the pitfalls ad-ridden “top hit” websites.

In preparation for an upcoming lesson, try this:

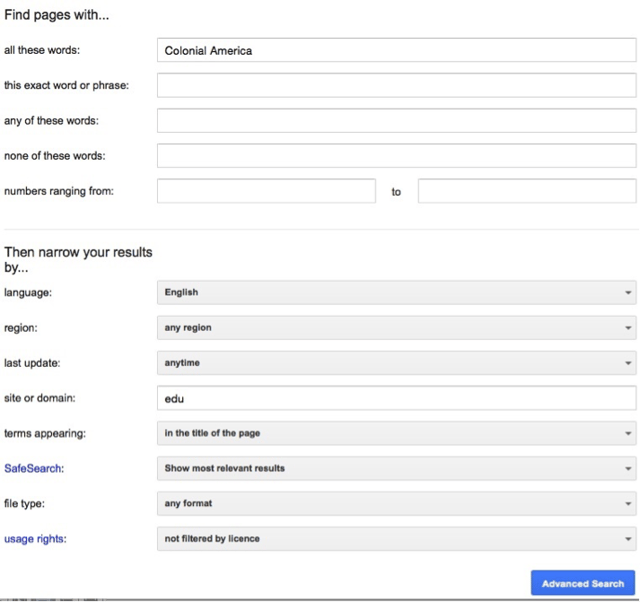

Begin by having students log on to IdeaPhora, and then open an advanced search window in Google. Then point out these fields under the section Find pages with…:

- all of these words

- this exact word or phrase

In the next section of the window, Then narrow your results by…, show students the fields:

- site or domain…and enter .edu or .gov

- terms appearing and select “in the title of the page”

In the example below, students search for resources related to Colonial America:

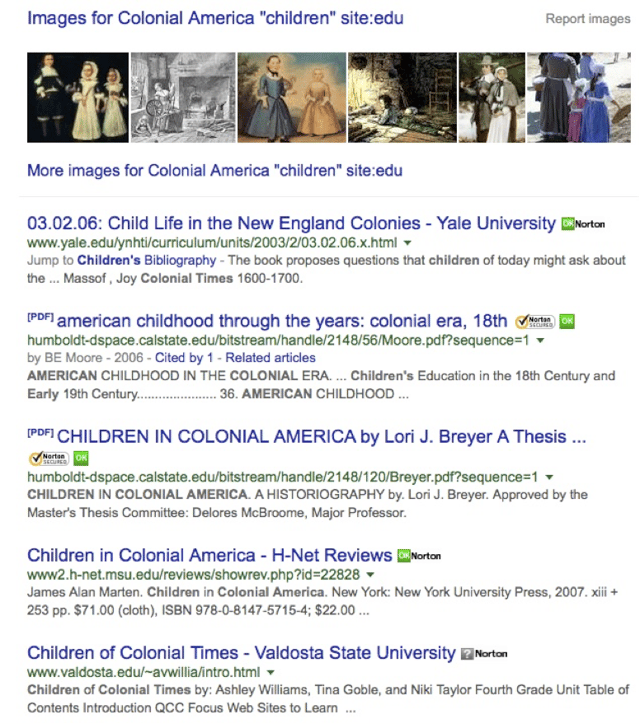

Before searching, you may wish to have individuals or groups enter more search terms in the field marked “this exact phrase,” (e.g., daily life, important figures, Native Americans, etc.). Using the word “children,” the Advanced Search generated a very targeted list, as well as images gleaned from the same sites:

As students find sites and images they find interesting, they can add them to Ideaphora as resources.

Because these results are limited education sites, they are more serious and less cluttered with distracting ads and animations. They have been internally vetted by institutions, and are most likely more reliable than commercial sites.

NOTE: Younger students can follow a less complex approach using this short-cut:

- Go to Google Images

- Enter key words

- Add the kind of site to which the search will be limited using a search operator (e.g., site: .edu OR site: .gov)

Such an activity introduces students to targeted web browsing. If you encourage them to compare and discuss results, they build their own “anticipatory set” by becoming familiarized with concepts and vocabulary in advance of the lesson. Their ownership in the unit’s creation may prompt them to become more engaged, ask better questions and come to a deeper understanding.

You’ll still have more activities to pursue as you examine the resources your class has brought to your attention, but you can be certain their role has been important and useful. Further, they are well on their way to digital curation, which we’ll discuss soon in my next post.

To try this lesson with Ideaphora, sign up for the Classroom Pilot Program.