This post is written by Mary Chase, Ph.D., an expert in curriculum design, literacy education, and technology integration.

Recently on this blog, we’ve been exploring an important brain function – visual learning – and the theories that suggest ways of helping students acquire associated learning strategies. Dual coding theory tells us that information that is encoded both visually and verbally is retained longer and in more complexity than mere words alone. Cognitive load theory demonstrates how information that is linked together through shared associations can enter long term memory as a single chunk, rather than bit by bit, making the learning process more efficient. This week, we’ll add another theory to our series about how learning takes place: constructivism.

According to constructivist theorists, we learn through experience and by reflecting on our experiences. Whenever we are faced with new information, we have to decide how it fits in with what we already know—or think we know. This approach is very different from simply memorizing facts and “banking” them mentally until we need them to succeed on a test.

In a constructivist classroom, the teacher is always guiding the students as they confront new information, helping them make sense of it, observing them as they accept new ideas and reject old ones. The educator models learning strategies and supports students as they integrate them into their repertoire of educational tools. All good learning reflects this approach, even at the earliest stages. Consider, for example, the roles of parents or other caregivers as they support very young children in language acquisition. Almost every child eventually learns how to communicate with words, and they do it without workbooks, formal lessons or assessments. They do it because someone is there to help them improve and celebrate their success. For example:

Child: Coo-eee!

Adult: Cookie?

Child: Coo-eee!

Adult: Can you say cookie? Coo-keee!

Child: Coo-keee!

Adult: Do you want a cookie?

Child: Wan’ coo-keee!

Adult: Let’s get a cookie!

These successes take place every day in the lives of small children. Notice that the learning takes place based on what the child already knows and their understanding is refined by the mentoring adult. There’s less emphasis on errors and more on progress.

Further, this kind of learning happens for all of us all the time. We just don’t notice it. “Dialogic learning,” as some refer to it, demonstrates what cognitive theorist Lev Vygotsky called the Zone of Proximal Development (often abbreviated to ZoPed). The ZoPed defines that area where learning can take place—between what someone already knows or can do and what they could achieve with the help of a more skilled “other.” Learning isn’t purposeless and it doesn’t take place in a vacuum. It is a social act.

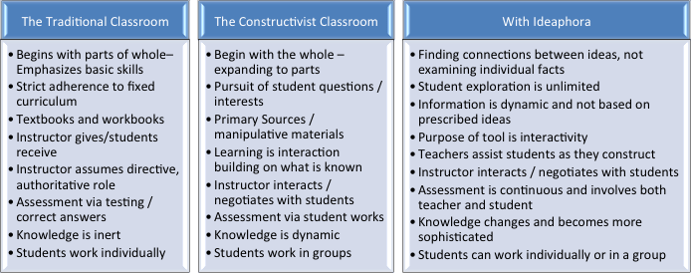

But what does this have to do with knowledge mapping? Below is a chart that compares traditional and constructivist learning, then constructivism augmented by the Ideaphora knowledge mapping environment:

Clearly, Ideaphora lends itself to constructivist approaches to learning: individualized, dynamic and effective. While concept mapping is certainly useful in a traditional classroom, it comes to life in situations where teachers mentor students and guide their learning, regardless of their backgrounds and differences in ability.

Would you like to try Ideaphora? Sign up to participate in the free private beta to explore the features and open education resources while creating your first map! Ideaphora also offers a Classroom Pilot program if you’d like to use it with your students.