This post is written by Mary Chase, Ph.D., an expert in curriculum design, literacy education, and technology integration.

It’s been a long time since I was a student, yet every year as autumn approaches I become nostalgic for the days when my only job was learning. I’ve been very fortunate in my teachers, but the highlight of my student days was surely the three years I spent at the University of New Hampshire studying under the guidance of Donald Graves and Jane Hansen. I ended up with a lot more than a Ph.D.

In the late 1980’s, literacy studies were undergoing a renaissance, and UNH, home of the Reading and Writing Process Lab, was at its center. Graves and Hansen were pioneers in new pedagogies that emphasized students’ abilities rather than their deficits. They also knew every other literacy guru—Jerry Harste, Ken and Yetta Goodman, Frank Smith—and made sure that we knew them too. One of the most influential for me was Louise Rosenblatt, author of The Reader, The Text, The Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work.

Rosenblatt focused on the role of the reader. “Text,” she writes, “is just ink on a page until a reader comes along and gives it life.” For her, the reader rather than the text was the soul of reading. Text is set in stone. It is the same every time we open a book. The reader, however, is always different and because of the idiosyncratic differences among readers—especially in terms of background knowledge—each of us experiences a text differently. How can that be tested at a level beyond the most basic facts? Further, individual readers change over time; therefore, we can never really read the same book twice. The text may remain the same on the page, but the reader has a different experience with each subsequent re-reading. Rosenblatt states:

"The reader brings to the work personality traits, memories of past events, present needs and preoccupations, a particular mood of the moment and a particular physical condition. These and many other elements in a never-to-be-duplicated combination determine his response to the text."

Perhaps that is why second readings of some books are disappointing while true classics are so eminently re-readable.

Further, readers approach texts with different stances along the continuum from efferent (user manuals, for example) to aesthetic (a good novel). These stances or attitudes depend a good deal on the readers’ prior experiences, successes and failures, interests and so on. What is aesthetic for one reader may be efferent for another.

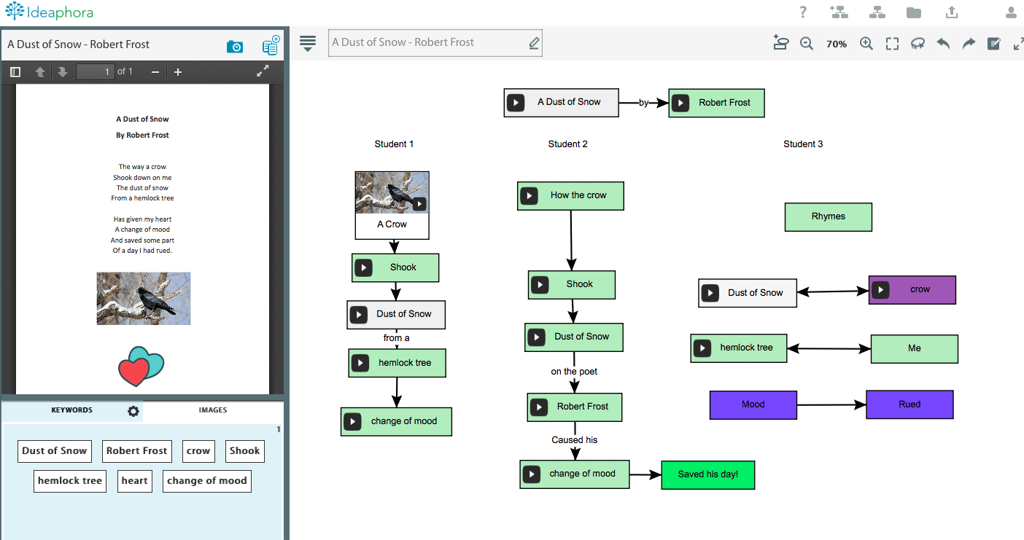

The difficulty for classroom teachers as they struggle to support their students is that the reading process is largely invisible. Students may frown, knit their brows, smile—but we’re never really sure what’s going on in their brains as they encounter reading tasks. This is a place where Ideaphora can help reveal a student’s route through a text and demonstrate a range of understanding and interpretation among members of a class. Consider these initial interpretations of Robert Frost’s “Dust of Snow”:

Dust of Snow

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

– Robert Frost

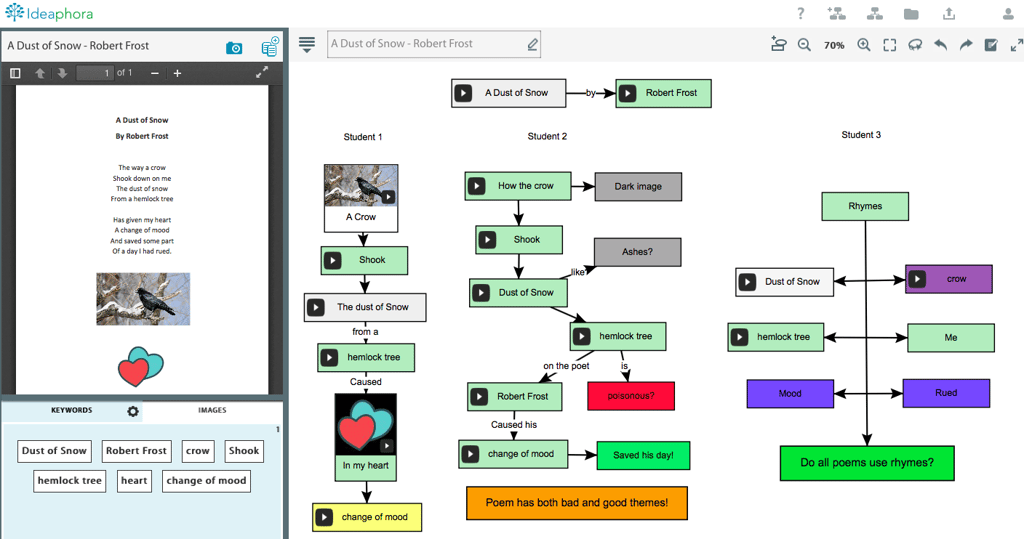

Three different students approach the poem at very different levels of sophistication. When they encounter the poem again and are asked to revise their initial responses, we can see the changes:

All of the student maps are enhanced but in different ways. Student 1 remains a literalist, but has made a slight step toward understanding figurative language. On a second reading, Student 2 has more sophisticated insights. Student 3 remains focused on poetic tools.

There’s more to Rosenblatt’s transactional theories of course, but this example does provide a tool for documenting student growth over time. If you have other ideas, we hope you’ll share them with us.

To try Mary's strategies and use Ideaphora with your students, enroll in the free Classroom Pilot Program.